NYU Master of Arts in Literary Translation: French – English

Accomplishments & Highlights

Three years after its creation by Emmanuelle Ertel, this one of a kind Masters program can boast a myriad of awards, grants, residencies and publications among its graduates, a large majority of who have pursued careers directly related to French and/or translation. Bolstered by courses taught by NYU professors including Eugene Nicole, Richard Sieburth, and Judith Miller, as well as invaluable mentoring by Emmanuelle Ertel and workshop leader Alyson Waters, the program’s alumni have been recognized by institutions such as Pen America and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, and have signed publication contracts with prestigious publishers such as New Directions, the New Press, Coach House Books, and Yale University Press. Here are a few highlights, organized alphabetically:

Chris Clarke (2012):

Chris is currently pursuing a PhD in French (with a declared specialization in translation studies) at CUNY; he spent the last year in Paris on an exchange with Paris X Nanterre, where he taught as a Maître de Langue. His translation publications include excerpts from Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, published by New Directions in 2013, and “The Stations of the Cry,” by Olivier Salon, published by Words Without Borders in 2013. In June, Chris received a research grant to spend ten days at the Queneau archives in Belgium. He is an associated member of an Oulipo-themed research seminar/group based in France, which is a joint project between Paris III, Lyon and Oxford. He will be heading up one of the groups for the digitization and encoding of the Oulipo archives.

Chris’ upcoming projects include two books for Wakefield Press, as well as shorter translations of work by Olivier Salon. He is also preparing translations for a potential anthology of selected works by Raymond Queneau.

Emily DeLong Harris (2014):

This fall, Emily heads to Paris where she will take MA classes in French literature at Université Paris 4/La Sorbonne.

Heidi Denman (2012):

Heidi translated Incandescences by Pius Ngandu Nkashama for Professor Nkashama P. Ngandu at LSU for possible publication.

Serene Hakim (2013):

Serene is based in Boston, where she previously interned at David R. Godine, Publisher. Her duties included working closely with the editor and reading French books to be potentially translated. Serene currently works for a literary agent.

Christiana Hill (2013):

Christiana received a French Voices award in 2014 for her translation of Agnès Desarthe’s Partie de chasse, which she has submitted to several publishers. She also worked at Geotext Translations, a translation company that specializes in legal translation. Her duties included evaluation of documents to be translated for language, cost, and any formatting concerns. She also assisted with reviewing French>English translations.

This fall, Christiana begins SUNY Binghamton’s PhD program in Translation Studies (within the Comparative Literature department), for which she received full tuition and a 3-year teaching stipend.

Allison Schein (2012):

Allison’s co-translation of Marie-Monique Robin’s Our Daily Poison, translated with fellow NYU alumnus Lara Vergnaud, is forthcoming from the New Press in November 2014. The French Cultural Services awarded the translated book a Hemingway Grant in 2014.

Allison has been working with author Paul Kix, translating French-language source material, including works by François de La Rochefoucauld, for research purposes. She is also working on her translation of a play that is on its third run in Paris and is still touring around Europe: Haïm: à la lumière d’un violon.

In addition to her translation endeavors, Allison works at Chanel as a paralegal/translator. Allison reports that her experience at NYU was integral to her being hired, and that because of her translation background, she has benefited from a number of great opportunities within the company, including working directly with the CEO on translations of speeches and internal communications.

Yareli Servin (2014):

Yareli as working as a project manager for Akorbi, a Texas-based translation company.

Victoria Sheehan (2014):

Recent graduate Victoria is awaiting news on a position for the international translation company, Transperfect.

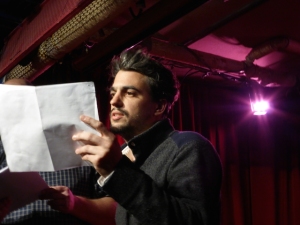

Patrick Stancil (2013):

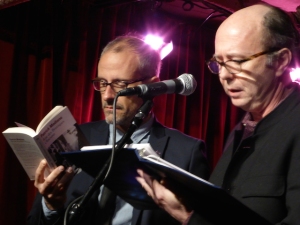

Patrick received a French Voices Award in 2014, and was short-listed for the grand prize, for his translation of Cyrille Martinez’s Deux jeunes artistes au chômage, which is being published on October 14, 2014 by Coach House Press as “The Sleepworker.” He also translated two children’s books on architecture that are forthcoming from Princeton Architectural Press.

In addition to his translation endeavors, Patrick works at New York University as an administrative aid at the Institute of French Studies. He recently participated in a panel at the Brooklyn Book Festival and will be attending the launch of “The Sleepworker” in Toronto in October. In November, he will be reading signing copies of his translation at the NYU bookstore.

Hannah Stell (2013):

Hannah works as a translation project manager for TransPerfect (receiving translation jobs from Sales, identifying the type of text and booking appropriate translators, and doing the final proofread of the file before delivery). Her most recent translation was a paid commission for the writer Francois Bon.

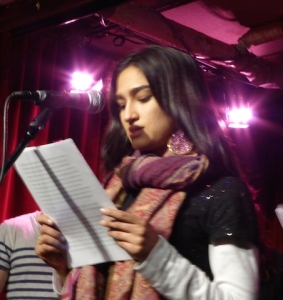

Sophia Tejeiro (2012):

Sophie’s translation of a play by Hervé Blutsch, GIZON, was staged at the Cornelia Street Café in 2012. Shortly after graduating, Sophie moved to France to work as a teaching assistant, and also participated in the Bus Bilingue project as an afterschool English teacher.

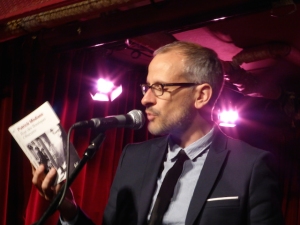

Lara Vergnaud (2012):

Lara received a PEN/Heim Translation award in 2013 for her translation of Zahia Rahmani’s France, story of a childhood, which was her thesis translation while at NYU. She has since signed a publication contract for the work with Yale University Press; the translation is forthcoming in 2015. Her co-translation of Marie-Monique Robin’s Our Daily Poison, translated with fellow NYU alumnus Allison Schein, is forthcoming from the New Press in November 2014.

Lara’s translations have appeared in Inventory, Pen America, Salon II, TWO LINES, and The Brooklyn Rail. In 2012, she was invited to participate in a translator’s residency in Lagrasse, France coordinated by l’Ecole de Litterature.

Peter Vorissis (2012):

Peter translated a book for the film industry after graduating, as well as excerpts of a graphic novel that were published by The Brooklyn Rail. This fall, he begins a PhD program in Comparative Literature (focusing on French, English, Greek, and translation) at the University of Michigan.

Margaret Yang (2013):

Margaret has done freelance translation work for a NYU journalism professor who is working on a book, which draws from extensive correspondence in French; Margaret translated about 125 letters from French to English.